MasterChef of Investing

In the popular TV program MasterChef, contestants face a series of cooking challenges. From low quality ingredients to inadequate preparation to poor implementation, so many things can, and do, go wrong. It’s a bit like investing.

In the world of investment, there customarily are two broad approaches. The first is some form of stock picking or market timing: managers attempt to find mispriced securities or seek to time their entry and exit points from various parts of the market.

This first approach is akin to the MasterChef challenge, which requires inventing a new and distinctive dish within a set time frame. The apparent advantage for the chef is flexibility of concept.

But what usually happens is that once the chefs have committed to a chosen recipe, they end up racing against the clock and are locked into particular ingredients to create a single dish. Of course, it may work out, but if they lose attention for a second, the dish is ruined and they have nothing to fall back on.

Likewise, in the investment world, the stock picker locks onto an individual idea. This single-mindedness actually results in little flexibility and creates time constraints. The manager tries to trade on information he believes is not reflected in prices, but if he errs, there may not be a Plan B.

If your primary goal is to stand out from the crowd, you are going to build cost and complexity into your process. In the cooking analogy, the price of your ingredients (out-of-season avocados, for example) is going to be a secondary consideration to having an impact. And once you’re committed to your distinctive dish (and high-cost ingredients), you may not be able to turn back.

The second approach to investing is when the investment manager seeks to track as closely as possible to a commercial index. The goal here is not to stand out. This results in the manager being most conscious of “tracking error” (or the deviation from the benchmark).

This approach is more akin to the MasterChef challenge in which contestants must cook a standard, popular dish with set ingredients. The focus is not creativity but following an established process as dictated by an outside party.

The ostensible advantage of the second approach is the chefs don’t have to create something completely new. The ingredients (or securities, in the case of the investment manager) are known. It is just a matter of assembling them.

However, the drawback of this latter approach is the absence of flexibility. The contestants can’t substitute one ingredient—or stock—for another. The recipe must be followed. What’s more, it must be achieved in a designated timeframe.

But what if we had a system that combined the creativity of the first approach with the simplicity of the second?

In this third approach, our contestants do not face unnecessary constraints in terms of either time or ingredients. Instead, they assemble a broad selection of dishes from multiple ingredients appropriate for the season and at times of their choosing.

The difference under this third way is that the chefs can focus on what they can control and eliminate elements that might restrict their choices. After all, their ultimate goal is to efficiently and consistently provide meals that suit a range of palates.

In the world of investing, we believe this third way is the optimal approach. Picking stocks and timing the market, like making brilliant, off-the-cuff meals in any conditions and in an efficient and consistent manner, is a tough task—even for the masters. Cooking meals off a provided menu, like the index managers, can be inflexible, costly and unappetizing

The third way of investing is akin to the strategy followed by TAGStone Capital through its asset allocation strategy and the strategic asset class funds it chooses.

This strategy allows us to design highly diverse portfolios that pursue market premiums with built-in flexibility that efficiently and consistently serve up investment solutions for a wide range of needs.

Call it the MasterChef of investing.

Future Unknown Innovations

We have made the point in this space before about the pace of innovation and its incalculable impact on the value of companies and, by association, stocks. It is an esoteric point to be sure. And yet it is very real. To see its impact, look no further than the following headline:

Apple to Replace AT&T in Dow Jones Industrial Average

– Forbes, March 6, 2015

It wasn’t so very long ago that the shine on Apple, Inc. had faded to a dull gray. The company’s signature Macintosh line of computers had been relegated to a cult following among graphic designers. Serious business users almost all defaulted to Microsoft’s PC platform and its market-dominating Windows software program. For much of the late 1980s and early 1990s, Apple was notable primarily as a grad school case study on the dangers of failing to properly leverage your technology.

Future Unknown Innovations (continued)

Bill Gates had won. Steve Jobs had lost. End of story.

Or not.

In June 2007, Apple unveiled the first iPhone. A mere eight years later, the company has transformed the way the world works, lives and communicates. Desktop computers are now principally tools for drafting long documents and creating spreadsheets. If you asked most folks if they’d rather go a week without their desktop or their smart phone… we all know the answer, don’t we?

The culmination of Apple’s resurgence came this past March, when the company supplanted the venerable AT&T in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Apple’s market capitalization today stands at around $735 billion – more than twice that of Microsoft – and it has a staggering $180 billion in cash reserves. (By comparison, the U.S. Treasury has $46 billion.) Its stock price has risen about 10,000 percent in the past ten years.

We point all this out not as a valentine to Apple, but as an example of how insufficient it is to analyze current known innovations when trying to assess future unknown innovations and, by extension future stock prices. In the early 2000s, when most analysts were encouraging investors to dump Apple stock, they were assessing what was known about Apple at the time. They were looking at the present and the recent past. Who among them could have predicted the iPhone’s impact in the coming decade,

not just on the fortunes of Apple, but on the productivity of mankind? The answer, of course, is no one – because the iPhone at that time was just a distant glimmer in Steve Jobs’ eye.

We frequently hear the argument made about valuations being “too high” in the stock market. Earnings, they say, don’t justify present stock valuations.

There is no doubt that the stock market moves in fits and starts, and corrections do occur periodically to curb “irrational exuberance” in the market. But it is also important to remember that future unknown innovations radically alter the fortunes of companies and, by association, their stock prices. And, it is this incessant innovation that our free market system encourages that has led the stock market to ever higher levels.

Staying the Course

For some long-time readers, you may have realized that the title of this last section seems to stay the same. This is not for lack of creativity, but to stress the importance of “staying the course.”

We feel this repetition is needed to provide a balance against the constant noise from the financial media, brokerage houses and our own emotions to constantly trade, churn and change our investment strategies.

As we have said before, one of the most important aspects of a successful investment strategy is to find an asset allocation between stocks and bonds that you can stick with through market highs and lows.

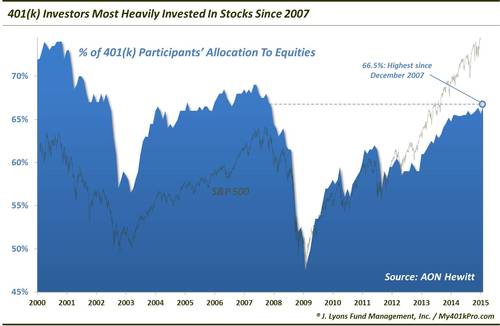

The reason for this is illustrated so well from a recent bit of news this quarter from retirement-industry consulting-giant, Aon/Hewitt.

The company, years ago, created an index that tracks the stock-to-bond ratio of the millions of 401(k) participants covered by the plans it consults.

The interesting news this quarter is that the index shows that the stock allocation percentage among 401(k) participants is now—just now—getting back to its pre-2008 levels.

The discouraging thing about this tidbit is that 401(k) participants have, in whole or in part, missed the huge market recovery that commenced in March 2009, when the Dow bottomed at 6,443. Only in the past couple of years, with the Dow north of 15,000, are 401(k) participants getting back to having the majority of their assets in stocks.

This is hardly the exception to the rule. Looking at the last fifteen years of the Aon/Hewitt 401(k) participant index, we see a long history of buying high and selling low.

Note the two low points of 401(k) participants’ stock allocation – the bottom of the bear markets in 2003 and 2009. Instead of rebalancing their portfolios back to their long-term allocations – which would have had the effect of buying stocks at lower share prices – 401(k) participants sold stocks.

Ideally, a graph like this should look perfectly flat. A participant’s 401(k) allocation between stocks and bonds should remain constant over time, changing only when he or she moves into new phases of life that require a more conservative long-term strategy.

This is a perfect example of the dangers of managing one’s own money. As we have said many times, the first job of a good wealth manager is to be the barrier between the client’s money and their emotions, because it is in the times of emotional extremes – both up and down – that the real damage is done to a portfolio.

Sadly, we need only look at the zig-zag disaster that is the Aon/Hewitt 401(k) index to know that this is true.

Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investments include risk and have the potential for loss as well as gain.

Data sources for returns and standard statistical data are provided by the sources referenced and are based on data obtained from recognized statistical services or other sources we believe to be reliable. However, some or all information has not been verified prior to the analysis, and we do not make any representations as to its accuracy or completeness. Any analysis nonfactual in nature constitutes only current opinions, which are subject to change. Benchmarks or indices are included for information purposes only to reflect the current market environment; no index is a directly tradable investment. There may be instances when consultant opinions regarding any fundamental or quantitative analysis do not agree.

The commentary contained herein has been compiled by W. Reid Culp, III from sources provided by TAGStone Capital, Capital Directions, DFA, Vanguard, Morningstar, as well as commentary provided by Mr. Culp, personally, and information independently obtained by Mr. Culp. The pronoun “we,” as used herein, references collectively the sources noted above.

TAGStone Capital, Inc. provides this update to convey general information about market conditions and not for the purpose of providing investment advice. Investment in any of the companies or sectors mentioned herein may not be appropriate for you. You should consult your advisor from TAGStone for investment advice regarding your own situation.