Blink Moments:

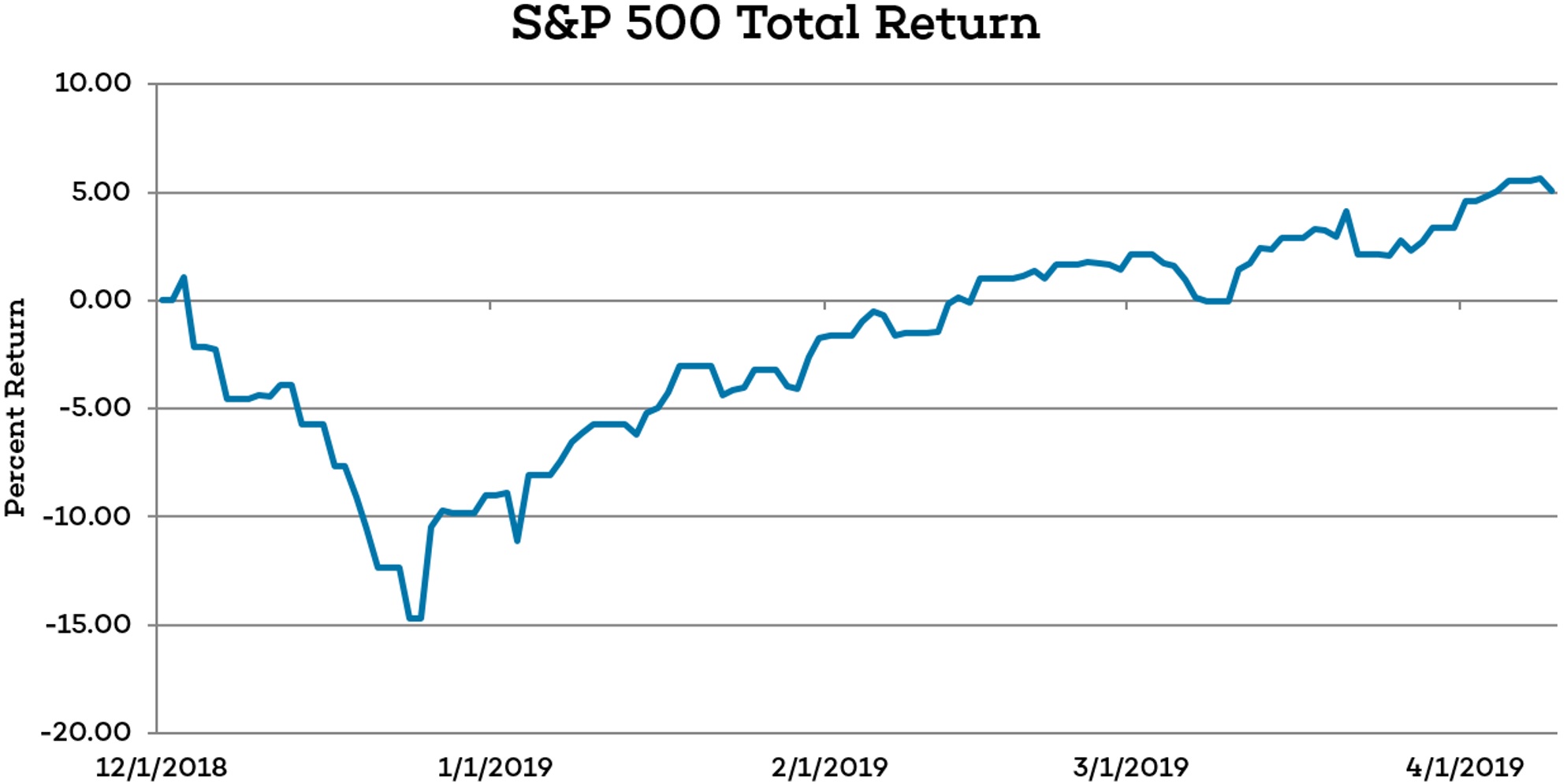

After a turbulent end to 2018 sent stock indices around the globe into bear-market territory, equities staged a big recovery in the first quarter of 2019. For the quarter, the S&P 500 index gained 13.65% and was within a few percentage points of its record high. The Russell 2000 small stock index gained even more, rising 14.58%. Large-cap foreign stocks, emerging markets stocks, and REIT (real estate) stocks enjoyed robust recoveries as well.

Alas, the many thousands of investors who bolted from the market in December weren’t along for the ride.

As markets swooned in December, according to Lipper, investors pulled $98 billion from U.S. equity funds, most of it coming late in the month after the steep selloff on Christmas Eve. The outflows weren’t just limited to stock funds. Morningstar estimates bond funds saw net outflows of $43 billion in December as investor anxiety about rising interest rates drove them to flee fixed income. Meanwhile, money-market funds saw their largest inflows since 2008, with a net $162 billion moving into that category in 2018.

In that regard, it should come as no surprise that stocks and, to a lesser extent, bonds saw a big rebound to start 2019. Individual investors have a long, sad history of doing exactly the wrong thing at the wrong time with their money. The events of the past six months have proved no exception.

On the other hand, more rational investors didn’t head for the exits in December, because they knew a 20% decline in stocks has historically occurred every 3-4 years. But most investors experience moments in their investment lifetimes when emotions overwhelm rational thought. We call these “blink moments.”

There have been many of them in just the past two decades: the bursting of the dot-com bubble, 9/11, and two bear markets in which stocks dropped more than 50%. These are a few of the big negative ones, but blink moments happen on the upside, too. The temptation to invest in dot-com stocks in the late 1990s, speculative real estate in 2006, or Bitcoin in 2017, was a siren song many investors couldn’t resist, and they paid dearly for it.

The Value of Wealth Counsel

Like many industries elsewhere in the world today, technology is commoditizing the investment management industry. However, this commoditization is missing the big picture. While analytics, plans, and platforms are certainly important tools in the wealth management process, they are just that—tools. It’s the relationship that you have with your wealth manager that really counts in blink moments. During these critical times when you don’t trust your own decision-making, many investors value the counsel they receive from a trusted person who knows their financial situation intimately.

It’s in these times, when emotions are at their peak, that investors face the greatest risk to their financial wellbeing. An important role of a wealth manager is to be the trusted buffer between the client and the whims of the stock market—the whims that separate many investors from their money.

Perils of Concentrated Stock Portfolios

For the better part of the 20th century, most investors followed a similar approach to constructing an investment portfolio. They used a stockbroker to buy a handful of stocks they liked (or that the broker convinced them to like) and held them in the portfolio for the long term.

Two things changed this dynamic in the 1970s. First, the long, deep economic slump in the United States during that decade introduced many investors to the downside of unsystematic risk—the risk you assume when you have a concentrated-stock portfolio that ties your investment fate to the fate of only a handful of companies. Many shareholders of U.S. auto, airline, and bank stocks found this out the hard way during that decade.

Second, this awakening of the investing public to the perils of concentrated-stock portfolios also coincided with mutual funds exploding onto the scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Mutual funds enabled investors to diversify away unsystematic risk by having exposure to hundreds of different securities in a single investment. As a result, in the ensuing four decades, mutual funds and ETFs became the preferred way for investors and their advisors to allocate investment assets. It’s rare today for long-term investors to concentrate new investment proceeds in just a handful of companies.

However, we still see three scenarios where certain investors come to us with a significant part of their net worth concentrated in one, or several, stocks:

- Businesses owners who have sold their company for stock in the acquiring company

- Heirs who have inherited large positions of low-basis stock

- Retired executives who have amassed significant amounts of stock in the companies they worked for through bonuses and options

The path to amassing these concentrated-stock positions is varied, but the resistance to diversifying away the unsystematic risk inherent in such positions generally falls into two categories. Either the investor opposes selling the positions and incurring capital gains taxes, or they have seen their concentrated-stock positions outperform the broad market and are convinced the outperformance will continue. Many times, it’s both.

We certainly sympathize with these concerns. It’s never fun to sell a stock that has performed well, or even adequately, and pay the resultant capital gains taxes. But it’s also not fun to have the misfortune of being trapped in a stock that suddenly experiences a dramatic downturn—sometimes temporary and sometimes permanent—due to circumstances in the company unrelated to the overall stock market.

Recent Examples of Single-Stock Risk

The financial news was rife with such examples in First Quarter 2019:

- Boeing: After a second crash of the aircraft manufacturer’s 737 MAX aircraft raised questions about the safety of the plane’s flight-management software, Boeing’s stock fell 18% over a three-week period in March.

- Kraft-Heinz: After an earnings miss by the consumer products giant raised investor fears that massive cost-cutting at the company was having an adverse effect on future profitability, the stock plunged 27% on February 22. Kraft-Heinz stock is now down nearly 50% since November and down 65% from its November 2017 high.

- Prada: The maker of handbags and other high-fashion accessories saw its shares drop 11% in a single trading session in March as consumer demand for the brand in China dropped dramatically.

Each of these unexpected downturns occurred while the broad stock market was surging. These are recent examples, but we have seen other heart-wrenching instances in the past twenty years of investors who were significantly affected by being in the wrong stock at the wrong time. Wachovia, Delta, Enron, WorldCom, GM, and Lehman come to mind. Investors who were once concentrated in these stocks would dearly love to turn back the clock and diversify their positions before the stocks experienced their unexpected downturns.

While diversifying concentrated-stock positions is emotionally and financially painful in the short term, it is a way of hedging against future, unknowable corporate missteps and misplaced gains. As Benjamin Franklin quipped a couple of centuries ago, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investments include risk and have the potential for loss as well as gain.

Data sources for returns and standard statistical data are provided by the sources referenced and are based on data obtained from recognized statistical services or other sources we believe to be reliable. However, some or all information has not been verified prior to the analysis, and we do not make any representations as to its accuracy or completeness. Any analysis nonfactual in nature constitutes only current opinions, which are subject to change. Benchmarks or indices are included for information purposes only to reflect the current market environment; no index is a directly tradable investment. There may be instances when consultant opinions regarding any fundamental or quantitative analysis do not agree.

The commentary contained herein has been compiled by W. Reid Culp, III from sources provided by TAGStone Capital, Capital Directions, DFA, Vanguard, Morningstar, as well as commentary provided by Mr. Culp, personally, and information independently obtained by Mr. Culp. The pronoun “we,” as used herein, references collectively the sources noted above.

TAGStone Capital, Inc. provides this update to convey general information about market conditions and not for the purpose of providing investment advice. Investment in any of the companies or sectors mentioned herein may not be appropriate for you. You should consult your advisor from TAGStone for investment advice regarding your own situation.