Recent Market Correction

After a period of relative calm in the markets, in recent days the increase in volatility in the stock market has resulted in renewed anxiety for many investors.

From January 27 to February 8, the U.S. market (as measured by the S&P 500 Index) fell more than 10%, marking the first stock market correction in more than two years. A stock market correction is defined as a 10% decline from the previous high. The last correction was in January 2016, when the market fell 11% in the worst start to any year on record. The recent correction has left many investors wondering what the future holds and if they should make changes to their portfolios.

While it may be difficult to remain calm during a substantial market decline, it is important to remember that volatility is a normal part of investing. Additionally, for long-term investors, reacting emotionally to volatile markets may be more detrimental to portfolio performance than the drawdown itself.

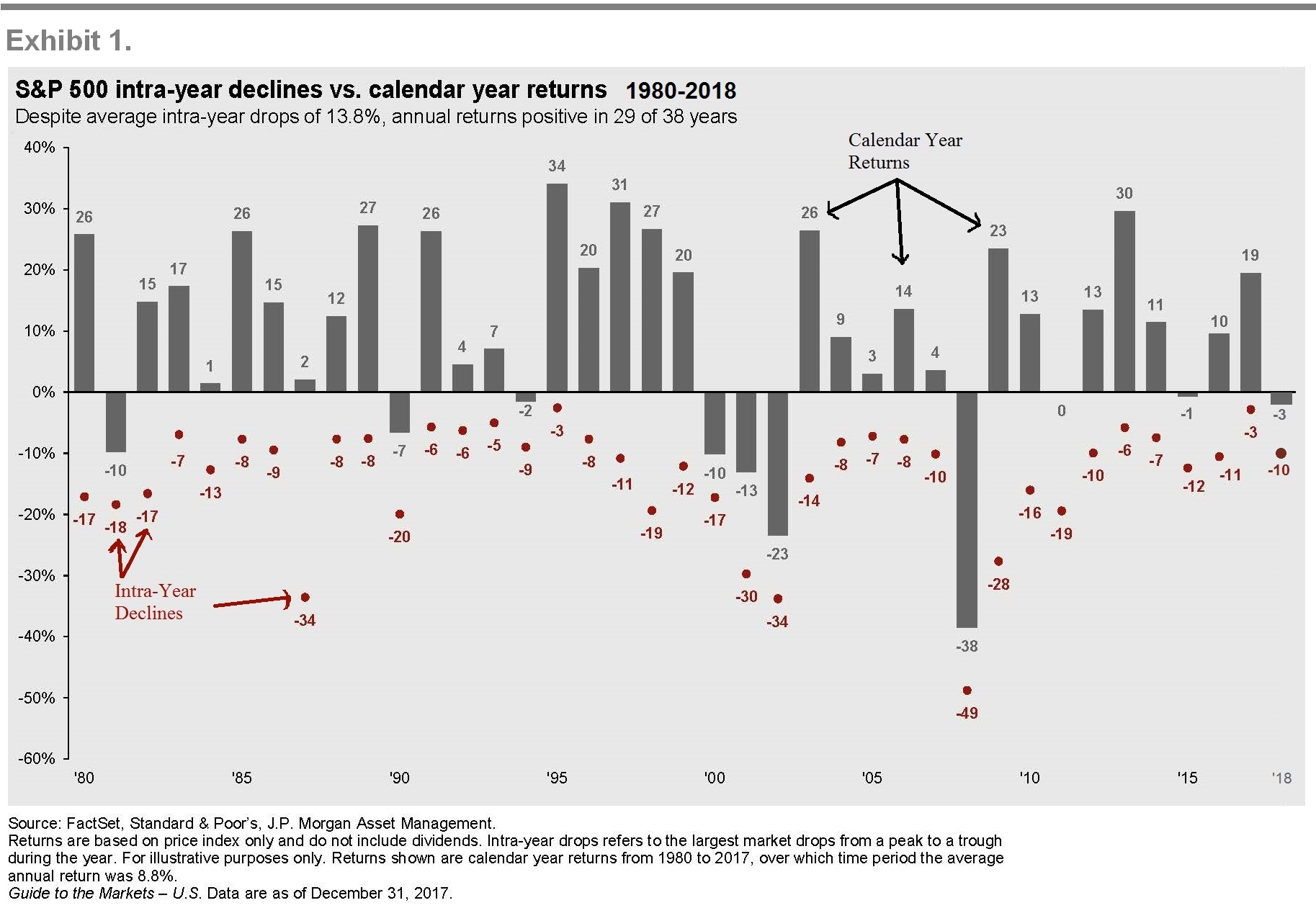

Intra-Year Declines

Exhibit 1 shows calendar year returns for the U.S. stock market since 1980, as well as the largest intra-year declines that occurred during each year. During this period, the average intra-year decline was about 14%. About half of the years observed had declines of more than 10%, and around a third had declines of more than 15%. Despite substantial intra-year drops, calendar year returns were positive in 29 years out of the 39 examined. This shows just how common market declines are and how difficult it is to say whether a large intra-year decline will result in negative returns over the entire year.1

Reacting Impacts Performance

If one was to try and time the market in order to avoid the potential losses associated with periods of increased volatility, would this help or hinder long-term performance? If current market prices aggregate the information and expectations of market participants, it should be difficult, if not impossible, to profitably time the market. In other words, it is unlikely that investors can successfully time the market, and if they do manage it, it may be a result of luck rather than skill.

It is also important to keep in mind that market timing generally involves both a buy and a sell decision. For example, if an investor believes the market is too high, the investor would need to decide when to sell. At a later point in time, the investor would need to make a decision when to buy back in. While it’s difficult to make a properly timed sell decision, it’s even more difficult to combine a properly timed sell decision with a properly timed buy decision.

When trying to time a market correction, it’s helpful to keep in mind a quote from the legendary Wall Street investor, Peter Lynch:

"Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections than has been lost in corrections themselves.”[2]

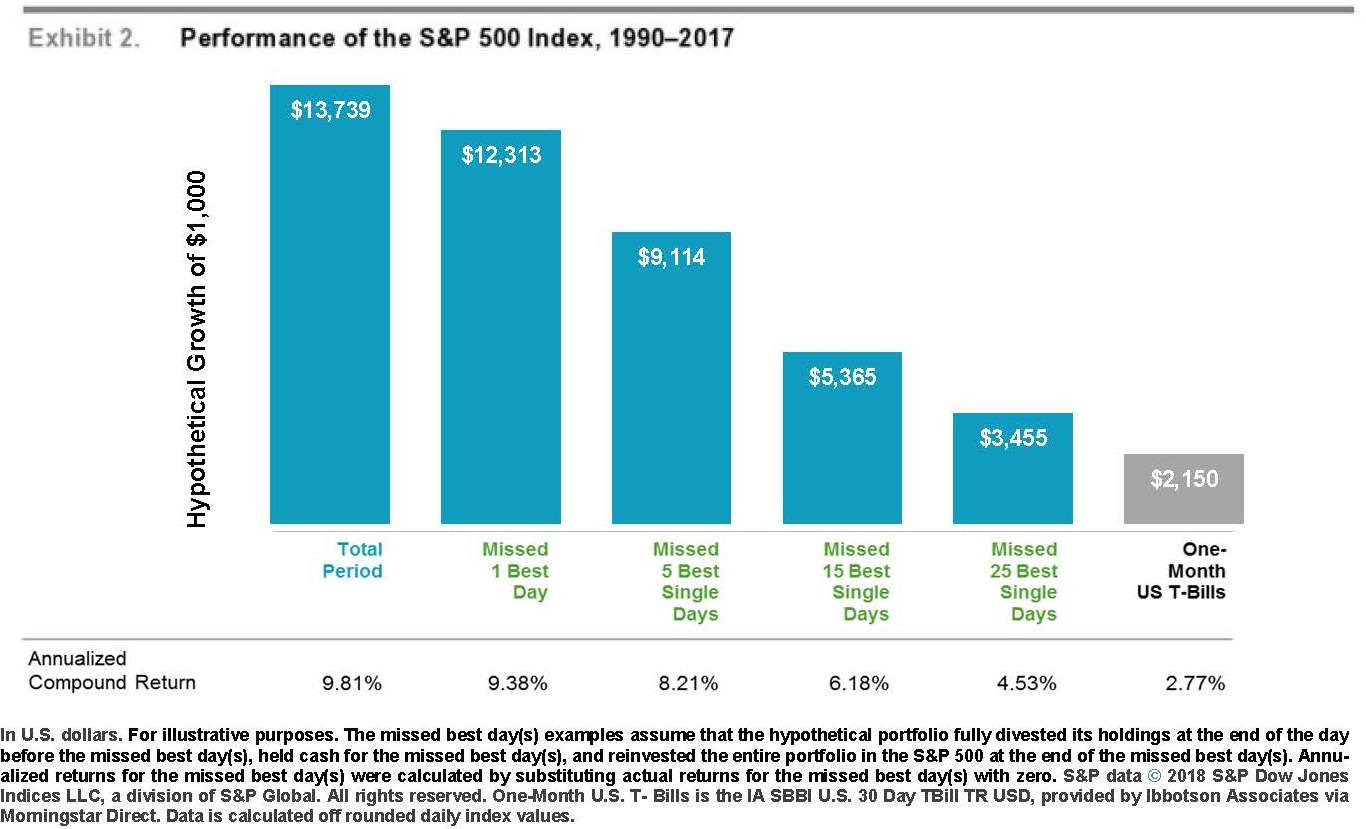

And We’re Only Talking a Few Days

Further complicating the prospect of market timing being additive to portfolio performance is the fact that a substantial proportion of the total return of stocks over long periods comes from just a handful of days. The inability of investors to be able to predict which days will have strong returns and which will not is another reason for investors to remain invested during periods of volatility rather than jump in and out of stocks. Otherwise, an investor runs the risk of being on the sidelines on days when returns happen to be strongly positive.

Exhibit 2 helps illustrate this point. It shows the annualized compound return of the S&P 500 Index going back to 1990 and illustrates the impact of missing out on just a few days of strong returns. The bars represent the hypothetical growth of $1,000 over the period and show what happened if you missed the best single day during the period and what happened if you missed a handful of the best single days. The data shows that being on the sidelines for only a few of the best single days in the market would have resulted in substantially lower returns than the total period had to offer.3

Asset Allocation Decision

The foundation of an investor’s investment plan should be a pre-determined ratio between stocks and bonds, also called an asset allocation. In general, the higher the ratio of stocks to bonds in an investor’s portfolio, the riskier the portfolio is considered to be since stocks generally have a greater risk of loss than bonds. The ratio should be set at a level that the investor can stick with through market ups and downs, based on their ability and willingness to take risk. The biggest risk that most individual investors face is the risk that they will sell out of their stocks at the bottom of a market cycle.

An investor’s hypothetical financial ability to bear a financial loss is easy to measure because it can be reduced to a mathematical conclusion based on the investor’s financial assets and time until they need the money. However, an investor’s “stomach” for volatility is more difficult to measure because most people don’t know how they will react when they see a significant drop in the price of stocks of 20%, 25%, or 30%. When times are good, like now, people become overconfident and many investors will overstate their willingness to withstand volatility.

Since there is a subjective nature to determining an investor’s ratio between stocks and bonds, two rules of thumbs may help:

Asset Allocation Decision (Continued)

1. When looking across the spectrum of all individual investors, the most common ratio is about 60% stocks and 40% bonds.

2. Younger investors are able to assume more risk since they have a longer time to make up a market downturn. So, one way to determine your ratio is to take 110 minus your age equals how much you should have in stocks (For example, 110 – 45 years old = 65% allocation to stocks).

Finally, Benjamin Graham, the great teacher of Warren Buffett, advocates in his book The Intelligent Investor (probably the most-respected investment book ever written) using a 50/50 stock/bond ratio as a baseline, and shifting as far as 25/75 in either direction, based upon current market conditions. Graham explains it this way:

"The sound reason for increasing the percentage in common stocks [beyond 50%] would be the appearance of ‘bargain price’ levels created in a protracted bear market. Conversely, sound procedure would call for reducing the common-stock component below 50% when in the judgment of the investor the market level has become dangerously high."

Systematic Rebalancing Helps

While the evidence has shown that it is difficult to use market timing to produce superior results, systematically rebalancing a portfolio is an important aspect of TAGStone’s investment process. Systematic rebalancing is designed to sell certain assets that have gone up above their target level and purchase certain assets that have gone down below their target level.

TAGStone is able to rebalance your portfolio periodically between stocks and bonds. If you have selected a 60/40 ratio, then 60% of your portfolio is allocated to stocks and 40% is allocated to bonds. If stocks go up, and your allocation to stocks goes to 75% of your portfolio for example, then TAGStone has the ability, after discussing with you, to sell a portion of your stocks that have increased in value and redeploy the proceeds into bonds.

In addition, some of the fund managers utilized by TAGStone periodically rebalance within the funds that they manage. This means, in general, they are selling stocks that have gone up in value and buying stocks at lower valuations based on predetermined market metrics.

For many investors, now is a relevant time to carefully consider rebalancing. The surge in stock prices over the last fourteen months has pushed up the stock allocation for many investors above their long-term target level. While it’s not pleasant to sell stocks when they are on an upward trend, momentum is a difficult factor to trade and trends can reverse at any point without a clear reason.

Staying Disciplined

With the recent volatility, investors may be asking themselves: “Is now a good time for me to revisit a change in my asset allocation?” An appropriate answer is highly dependent upon an investor’s unique situation and their risk and return objectives. For investors considering a change to their asset allocation, a disciplined approach with a long-term view is likely more prudent than making a decision based on a reaction to short-term market movements.

While market volatility can be nerve-racking for investors, reacting emotionally and changing long-term investment strategies in response to short-term declines could prove more harmful than helpful. By adhering to a well-thought-out investment plan, ideally agreed upon in advance of periods of volatility, investors may be better able to remain calm during periods of short-term uncertainty.

Over the long term, the financial markets have rewarded investors. People expect a positive return on the capital they supply, and historically, the equity and bond markets have provided meaningful growth of wealth. As investors prepare for 2018 and what the year may bring, we should remember that frequent changes to an investment strategy can hurt performance. Rather than trying to time the market based on hunches, headlines, or indicators, investors, who pick and stay disciplined to an asset allocation, should benefit from expected long-term positive market returns.

1. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors, LP

2. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-smartest-things-ever-said-about-market-timing

3. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors, LP

Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investments include risk and have the potential for loss as well as gain.

Data sources for returns and standard statistical data are provided by the sources referenced and are based on data obtained from recognized statistical services or other sources we believe to be reliable. However, some or all information has not been verified prior to the analysis, and we do not make any representations as to its accuracy or completeness. Any analysis nonfactual in nature constitutes only current opinions, which are subject to change. Benchmarks or indices are included for information purposes only to reflect the current market environment; no index is a directly tradable investment. There may be instances when consultant opinions regarding any fundamental or quantitative analysis do not agree.

The commentary contained herein has been compiled by W. Reid Culp, III from sources provided by TAGStone Capital, Capital Directions, DFA, Vanguard, Morningstar, as well as commentary provided by Mr. Culp, personally, and information independently obtained by Mr. Culp. The pronoun “we,” as used herein, references collectively the sources noted above.

TAGStone Capital, Inc. provides this update to convey general information about market conditions and not for the purpose of providing investment advice. Investment in any of the companies or sectors mentioned herein may not be appropriate for you. You should consult your advisor from TAGStone for investment advice regarding your own situation.